- Home

- About us

- Laboratories

- Central Nervous System Physiology

- Central Nervous System functions compensation Physiology

- Immunology and Tissue Engineering

- Smooth Muscle Physiology

- Toxinology and Molecular Systematics

- Sensorimotor Integration

- Laboratory of Histochemistry and Morphology

- Human Psychophysiology

- Integrative Biology

- Purification, Certification and Standardization of Physiologically active substances

- Neuroendocrine Relationships

- Distance Լearning Center

- Laboratory of Hyperspectral Imaging of Surgical Targets

- Biophysics Lab

- News & Events

- Master's Program

- Research

- Councils

- Contact Us

- OIPH Docs

L. A. Orbeli Institute of

Physiology NAS RA

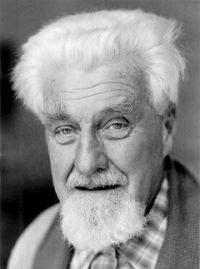

The exhibition hall is dedicated to the Armenian period of Konrad Lorenz.

“Soviet people were starving, but they shared with the prisoners the little they had”.

Konrad Lorenz

It is difficult to discuss such a vast subject within a single exhibition in such a short period of time. Nevertheless, I would like to present some of my findings and conclusions.

The purpose of my research was to understand what had happened in the Armenian camp, to construct a picture as complete as possible. The research was carried out in Austria and Armenia and involved studying archive materials in Armenia and Konrad Lorenz’s personal archive materials, conducting interviews, comparing different researchers’ results, as well as studying Konrad Lorenz’s work itself. Consequently, I came to conclusions which I will present further.

Konrad Lorenz started to focus on the issue of human essence and study it within the context of camp life, as in Armenia he was given the opportunity to work as a doctor, which gave him a sufficient amount of free time to work, write notes, and think(1). In addition, he had the chance to meet people outside of the camp, who lived in extremely harsh conditions. That was a society of first or second generation survivors of the Armenian Genocide (1915-1920), who, not even having recovered yet, were now confronted with the horrors of the Second World War. As Lorenz’s camp friend doctor Straube notes, “They loved Konrad Lorenz so much at the Armenian camp that the camp superintendent took him out for a walks, and, during these walks, they met people who needed a doctor, and, instead of paying Lorenz, they served him with delicious Armenian dishes. The same thing had happened to me. From time to time, I was called as a doctor, and women that had lost their children during the Great Patriotic War were sorry for me for being a war prisoner at such a young age. The tears of Armenian mothers shocked me, since our mothers back home cried the same way for us(2).

There was no ‘enemy camp’ any more. During that period, a human simply met another human, and everybody was in a deep grief—the war prisoners, mothers who had lost their sons, people who had become disabled as a result of the war and Soviet soldiers who, against their will, had to guard the prisoners. Moreover, there was the hunger, the illnesses and so forth.

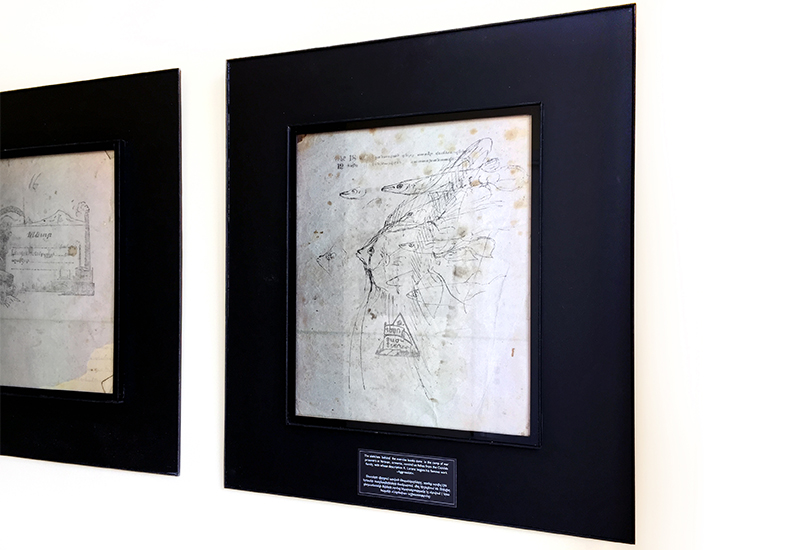

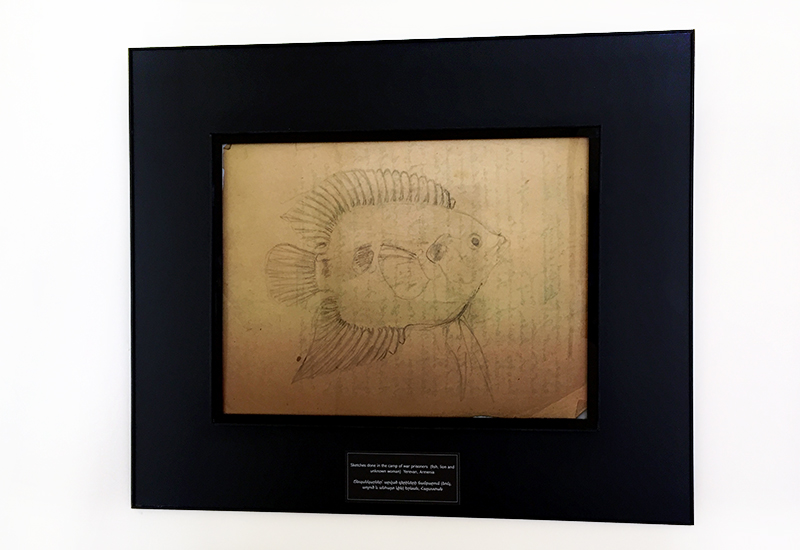

I think these—along with the situation inside the camp, where people became fully exposed along with their entire instinctual system—were the main reasons behind Lorenz’s tendency to thoroughly study the human. This forced Lorenz to work in conditions where even surviving was a difficult task. I think that it was as a result of tense and complex human relations inside the camp that the idea for his famous book “Aggression” was born. On It can be attested by Armenian school notebooks, which were found in Konrad Lorenz’s personal archives. At the back side of one of Armenian school notebooks, which were found in Konrad Lorenz’s personal archives, such copybooks he drew those fish species by which description he begins his famous book “Aggression”.

During my research, I came to another very important hypothesis conclusion— at the basis of the ideology of the ‘respect and mutual support of your own species,’ which are important values common to all mankind and are mentioned in Lorenz’s books a lot, may could be the strong human support which he received in Armenia, including. the exceptional treatment of the officer and camp doctor Hovsep Grigoryan. He let Lorenz make notes and work on his book, which was strictly prohibited for war prisoners. Furthermore, in the ‘Armenian Manuscripts’ found in the archive, we see that Lorenz did not only make write notes on bags of cement using permanganate solution, but most of his notes were made using could also use ink, pen, and pencil. This and the discovered school notebooks (at the time rare even in schools) imply the existence of someone’s (probably Hovsep Grigoryan’s) support. Finally, something virtually impossible had taken place: —according to Straube, H. Grigoryan had promised Lorenz to let him take his writings notes home with him. The camp administration made yet another unprecedented move. They allowed Lorenz to freely move outside of camp borders, and, during one of his walks, he met the famous architect Mark Grigoryan, who was then busy exploring the area for the purpose of building the Matenadaran building. Their conversation went well, and Lorenz told Grigoryan that before the war he had studied animals and was now dreaming to go back to his favorite occupation. Mark promised to talk to the camp administration and advised Lorenz to write a letter to the vice president of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Armenian scientist Levon Orbeli. Mark kept his promise, while Lorenz took his advice and wrote a letter to Orbeli. The camp administration gave a brilliant (for those times) reference letter, and Orbeli wrote a letter to Stalin, following based on which Lorenz was transported to a camp in Krasnogorsk, where the camp for privileged 'VIP' prisoners was located. There, he was allowed to type out the notes he had made in Armenia and asked to. He made two copies: one —the first was for the Soviet authorities and one, , and the second, as Lorenz noted, was for himself. Further on, after two months there, he was allowed to return to his homeland, taking with him his notes and the typewritten copy, which had not been subjected to any special censorship. Thus, we can assert that not only Lorenz’s works, but maybe also his life as well, were rescued, as the brutal camp life did not spare anyone. As Straube notes, ‘Maintaining war prisoners was extremely difficult, since they—the Armenians—had almost no food, and, during the period spent there by Lorenz, the prisoners ate only flour and, as a result, often got poisoned and subsequently developed severe forms of dystrophy. We tried to compensate for the deficit of food with nettle and dapple that grew on roadsides, but all in vain.’

These are the incredible events that the scientist went through in Armenia. We can guess what would happen to people who supported Lorenz during the Stalin regime if it was revealed that the manuscripts were essentially anti-Soviet, and this involved people who, yet a few months ago, were in a position to shoot at one another on the battlefield. I think that this very experience became the basis behind Lorenz’s strict criticism and sometimes even ridicule of the Fascist ideology, as well as for an emphasis on all-human mutual aid and vital significance of socialization in his further life and work, which, however, requires a separate research.

P.S. Apart from his manuscripts, Lorenz brought home from Armenia two birds, a starling and a lark, in self-made cages, a smoking pipe made of a corn cob, and a wooden duck figure, which he had carved for his wife. All of these items were carefully preserved by Lorenz and have stayed unharmed up to now thanks to his descendants.

The text was been written for the exhibition which was been in Austria 19/09/2016.

Additional References

- Konrad Lorenz’s autobiography. which was written in 1973 and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes.

- Straube Werner, Memories about Konrad Lorenz. Symposium on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Konrad Lorenz, Nov. 2003, Vienna.

- Konrad Lorenz’s personal archives

- National Archives of Armenia

- Elena Gorokhovskaya “History Courses”

- Valeriy Gasparyan “The Armenian Odyssey of Nobel Lorenz”

- Ashot Sagratyan “Where Memory Begins”

- Hamlet Mirzoyan “The Story of Two Dynasties”, № 3 (162) February (1-15) 2011.

- Interview with Dr. Wolfgang Schleidt, a friend and colleague of Konrad Lorenz.

I would like to thank ‘Kulturkontakt’ organization and Austrian Ministry of Culture, the State Museum of Nature of Armenia, and the administration and staff of the National Archives of Armenia, curator, art critic Susanna Gyulamiryan,Lili Amroyan. Thanks to Dr. Wolfgang Schleidt. Special thanks to the descendants of Konrad Lorenz, especially Riccardo Draghi-Lorenz.

Special thanks to the physiological Institute after Orbeli for the exhibition hall realization, especially to the director Dr. Naira Ayvazyan, also Hovnan Qartashyan and Art Laboratory NGO. The exhibition hall is dedicated to the Armenian period of Konrad Lorenz.

Edgar Amroyan